Journal of Pharmaceutical Research

DOI: 10.18579/jopcr/v24.i4.130

Year: 2025, Volume: 24, Issue: 4, Pages: 224-230

Original Article

Sharon Barachel Papang1, Kedovilie Kuotsu1, Sanskar Pradhan1, Jyoti Timsina1, Suikriti Sharma1, Ananya Bhattacharjee2*

1Himalayan Pharmacy Institute, Rangpo, Majhitar, East Sikkim, 737136, India

2Associate Professor, Pharmacology Department, Himalayan Pharmacy Institute, Rangpo, Majhitar, East Sikkim, 737136, India

*Corresponding author.

Ananya Bhattacharjee

Email: [email protected]

The aim of the study was to evaluate the antispasmodic properties of the leaves of Urtica dioica. The gastrointestinal tract plays a vital role in consuming and digesting food, absorbing nutrients, and removing waste from the body. Various diseases affecting the GI system can adversely impact digestion and overall health. Common digestive issues include diarrhoea, IBS (Irritable Bowel Syndrome), constipation, peptic ulcers, and other gastrointestinal disorders. GIT disorders encompass any ailments that influence the gastrointestinal tract, including symptoms that arise in the middle or lower gastrointestinal system. The purpose of this study was to investigate the antispasmodic effects of Urtica dioica leaves on the voluntary motility and contractility of chicken ileum smooth muscle in vitro. The research utilized chicken ileum to evaluate the muscle-relaxing properties of Urtica dioica rhizomes on intestinal contractions. Traditional remedies for GIT disorders often involve the use of herbal treatments such as Zingiber officinale and Artemisia vulgaris. Consequently, this study determined that the ethanolic extract of Urtica dioica exhibits antispasmodic properties in intestinal tissue, indicating its potential application as an antidiarrheal agent.

Keywords: <I>Urtica dioica</I>, Antispasmodic, Gastrointestinal disorders, Chicken ileum, Antidiarrheal agent

The gastrointestinal (GI) system consists of the digestive tract and a series of accessory organs. The tract extends from the oral cavity through the pharynx, oesophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and terminates at the anal canal. The accessory organs include the teeth and the tongue, as well as glandular organs such as the salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas [1].

Together, these components perform essential physiological functions: ingestion, digestion, absorption of vital nutrients, secretion of necessary enzymes and fluids, and ultimately Excretion of undigested food remnants from the body [2]. The gastrointestinal tract (GIT) relies on a precisely regulated sequence of muscular movements - segmental and peristaltic contractions - to perform its functions effectively [3].

The motor functions of the gastrointestinal tract are facilitated by two layers of smooth muscle within its wall: an inner circular layer and an outer longitudinal layer. These layers work together to generate coordinated contractions that enable the movement of contents through the digestive system [4]. This motility pattern in the small intestine is predominantly controlled by the enteric nervous system, which coordinates local mixing and propulsive movements essential for digestion and nutrient absorption., with neurotransmitters like acetylcholine playing a key excitatory role in stimulating smooth muscle contraction [5]. Disruptions in these processes underlie a variety of gastrointestinal disorders [6].

The pharmacological management of gastrointestinal disorders is often accompanied by a range of adverse effects. In response to these concerns, there has been growing patient interest in herbal remedies [7].

Across civilizations, herbal remedies have served as the cornerstone of therapeutic practice, evolving through empirical knowledge inherited from ancestors. These traditional systems, rooted in the medicinal flora of each region, continue to inform modern approaches to natural and integrative healthcare [8].

Many plants have been studied and reported to have the potential to treat gastrointestinal disorders. For example, Radix aucklandiae, Zygophyllum gaetulum, Prangos ferulacea, Allium elburzense, Plectranthus barbatus, Thymus vulgaris, Artemisia vulgaris, Matricaria recutita, Galphimia glauca, Allium cepa, Eucalyptus camaldulensis, Viburnum prunifolium, Phyllanthus emblica and Acorus calamus were found to have antispasmodic property [9-23].

It has been observed that these plants and herbs contain bioactive compounds, including flavonoids and tannins, which exert therapeutic impact on the human body.

Urtica dioica, commonly known as stinging nettle, is a perennial herb renowned for its wide range of medicinal and nutritional properties. It is from the Urticaceae family, long valued for both its nutritional and medicinal properties. Traditionally, the roots have been used as diuretics, astringents, anthelmintics and in the treatment of ailments such as cough, cold, jaundice, and asthma. Additionally, leaf paste is traditionally used to treat diarrhoea and dysentery [24].

Phytochemicals, including flavonoids, phenolic acids, amino acids, carotenoids, organic acids, and fatty acids are reported from the different plant parts of Urtica dioica [25]. The different flavonoids present in stinging nettle such as apigenin, luteolin and quercetin have been proven to have antispasmodic property [24, 26].

Hence, the aim of this study is to determine antispasmodic effects of Urtica dioica on spontaneous motility and contractility of the smooth muscle preparation of chicken in vitro.

All chemicals used were of analytical grade and purchased from standard companies. All the ingredients of solution were prepared freshly before the experiment.

Urtica dioica leaves were collected from Lingmoo, South Sikkim. After the collection, they were washed and shade dried for 2 weeks. The leaves were then cut into small pieces and was grinded by using grinder. Then, they were prepared for extraction process ([Fig. 1]).

The leaves were air-dried in a shaded area to preserve their bioactive compounds for about 30 days and processed by grinding into fine powder in a blender. The powder was extracted using maceration with ethanol. For this purpose, 100 g of powder was macerated in 1 l of ethanol (70% the volume of the fraction) for three days with occasional stirring and the solution was then filtered using filter paper (Whatman No. 1) and then concentrated in a rotary evaporator at 40°C and stored at –20°C in the refrigerator for subsequent evaluation of anticholinergic activity [27].

Preliminary phytochemical screening was performed for alkaloids, flavonoids, glycosides, terpenoids, proteins, amino acids, saponins, volatile oils, carbohydrates and tannins by standard procedures [28, 29].

Segments of healthy chicken ileum were freshly collected from a local slaughterhouse. The ileum is the small intestinal segment extending from Meckel’s diverticulum to the ileo–caecal junction where the paired ceca begin. Terminal portions measuring approximately 1–1.5 cm in length were dissected and transferred into 30 mL organ baths containing Tyrode’s solution (NaCl, 40; KCl, 1; MgCl2, 5; NaH2PO4, 0.25; CaCl2, 1; NaHCO3, 5; glucose, 10).

The chicken ileum was maintained in Tyrode solution to preserve tissue viability during the experiment at 37 ± 2 °C and continuously oxygenated using an aerator. The tissue was then allowed to equilibrate in the organ bath for 30 minutes. Graded concentrations of acetylcholine (1, 2, and 4 µg/mL) were successively introduced into the bath to induce contractile responses, and control cumulative concentration–response curves were plotted.

Subsequently, a low dose (2 mg/mL) and a high dose (4 mg/mL) of the ethanolic extract of Urtica dioica, as well as atropine (2 µg/mL), were added separately to the organ bath 10 minutes prior to recording the corresponding concentration–response curves. Acetylcholine was then tested along with the plant extract and the standard antagonist (atropine). The anticholinergic activity of the extracts and atropine was assessed against a standardized effective dose of acetylcholine (1–4 µg/mL). The inhibitory effects on acetylcholine-induced contractions were subsequently represented graphically [30, 31].

Results of the preliminary phytochemical investigation of aqueous extract of Urtica dioica exhibited presence of flavonoids and tannins ([Table. 1]).

| Sl. No. | Test | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Flavonoids | +ve |

| 2 | Tannins | +ve |

| 3 | Alkaloids | +ve |

| 4 | Glycosides | +ve |

| 5 | Carbohydrates | +ve |

| 6 | Volatile oils | +ve |

| 7 | Amino acid | +ve |

| 8 | Saponins | +ve |

| 9 | Terpenoids | +ve |

The percentage yield of the extract was calculated as follows:

Weight of dried extract/ weight of dried leaf powder x 100 (w/w)

The percentage yield of Urtica dioica= (2.5/23.25) x100 = 10.75%

The environmental conditions maintained during the experiment were as follows: the bath volume was 30ml, speed of recording was 0.25mm/sec, equilibrium time was 30 minutes, the interval between dose is 1minute, and the dosing method was cumulative ([Table. 2]).

|

Experimental conditions |

|

|---|---|

| Bath volume (ml) | 30 |

| Speed of recording paper (mm/sec) | 0.25 |

| Equilibrium time (min) | 30 |

| Interval between dose (min) | 1 |

| dosing method | Cumulative |

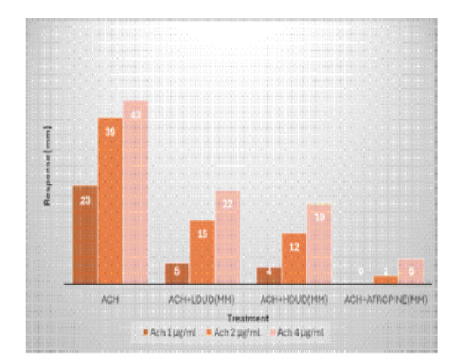

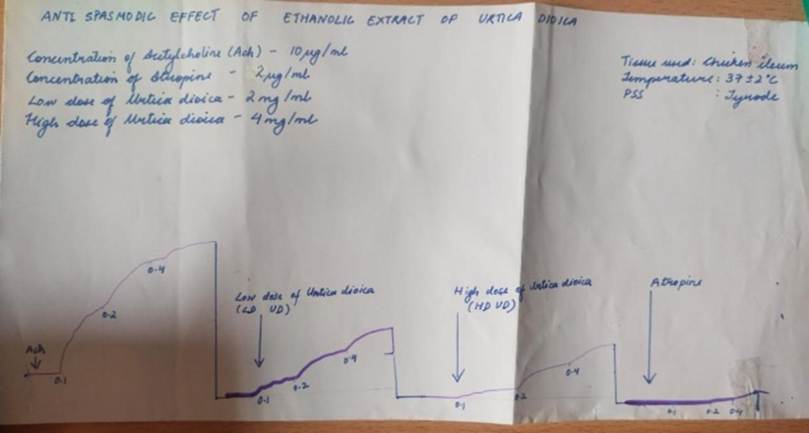

Concentration-response curve in [Fig. 4] showed that both 4 and 2mg/mL of Urtica dioica as well as 2µg/mL of atropine caused concentration dependent, decrease in contractile response as compared to concentration-response curve of Ach alone.

|

Treatment |

Response (in mm) |

|---|---|

| ACh 1 µg/mL |

23 |

|

ACh 2 µg/mL |

39 |

|

ACh 4 µg/mL |

43 |

| Treatment | Response (in mm) |

Ach + HDUD (in mm) |

Ach + LDUD (in mm) |

Ach + Atropine (in mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACh 1µg/mL | 23 | 4 | 5 | 0 |

| ACh 2 µg/mL | 39 | 12 | 15 | 2 |

| ACh 4 µg/mL | 43 | 19 | 22 | 6 |

According to the determination of EC50, EC50 of ACh alone was 1.99µg/mL. After the addition of 4 and 2mg/mL concentrations of Urtica dioica extract, the EC50 of ACh increased, indicating a reduction in acetylcholine potency in the presence of the extract. In the presence of HDUD and LDUD, EC50 were 5.49 and 3.6µg/mL respectively. EC50 of ACh in the presence of 2µg/mL atropine was 29.5µg/mL.

The peaks presented in [Fig. 5] showed the force of contractions in chicken ileum generated by graded doses of ACh from 1, 2 and 4 µg/mL. After addition of 4 and 2mg/mL of Urtica dioica as well as 2 µg/mL atropine, there were significant reductions in the peaks.

| Treatment | EC50 (µg/mL) |

|---|---|

| ACh 1-4µg/mL | 1.99 |

| Ach + HDUD 4mg/mL | 5.49 |

| Ach + LDUD 2mg/mL | 3.6 |

| Atropine 2µg/mL | 29.5 |

Herbal remedies have been integral to disease management and quality-of-life improvement since the earliest human civilizations [32].

The main objective of this study was to assess the antispasmodic effects of the ethanolic extract derived from the leaves of Urtica dioica, using isolated chicken ileum tissue as the experimental model. Acetylcholine (Ach) was observed to produce concentration-dependent contractions, with the maximum response recorded at 4 µg/mL. Prior to the administration of varying doses of the plant extract or the standard antagonist, the ileum tissue was rinsed for 3–5 minutes to restore contractility to baseline levels.

The concentration–response analysis revealed that Urtica dioica extract at both 2 mg/mL and 4 mg/mL, as well as atropine (2 µg/mL), produced a concentration- dependent inhibition of acetylcholine-induced contractions. The higher dose of the extract exhibited a more pronounced inhibitory effect compared to the lower dose.

It is well established that acetylcholine-induced intestinal contractions are predominantly through muscarinic M2 and M3 receptors present in intestinal smooth muscle. Binding of acetylcholine to M2 receptors reduces cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-mediated relaxation, while its interaction with M3 receptors stimulates phosphoinositide hydrolysis, resulting in muscle contraction [33].

The outcomes of this study suggest that Urtica dioica extract, similar to atropine, likely exerts its antispasmodic activity by inhibiting signaling through M2 and M3 muscarinic receptor pathways. Both concentrations of Urtica dioica extract and atropine, significantly reduced acetylcholine-induced contractile responses compared to acetylcholine alone. These findings support the idea that suppression of muscarinic receptor activity by the extract promotes intestinal smooth muscle relaxation and may contribute to the alleviation of gastrointestinal spasms. It is well-established that blocking the muscarinic receptors in the gastrointestinal tract leads to the relaxation of smooth muscles [34].

The EC50 (effective concentration required to produce half maximal response for acetylcholine (Ach) alone was determined to be 1.99 µg/mL. When given along with Urtica dioica extract, the EC50 value of Ach increased to 3.6 µg/mL with 2 mg/mL of extract and 5.49 µg/mL with 4 mg/mL of extract. By comparison, the addition of atropine (2 µg/mL) caused a marked shift in the EC50 of Ach to 29.5 µg/mL. The observed increase in EC50 implies that a greater concentration of Ach is required to elicit half of the maximal contraction, indicating that Urtica dioica extract attenuates Ach-induced intestinal contractions and demonstrates significant antispasmodic potential.

[Fig. 5] illustrates the contractile force of chicken ileum in response to increasing concentrations of acetylcholine (1, 2, and 4 µg/mL). A significant reduction in contraction amplitude was observed following the administration of Urtica dioica extract at 2 mg/mL and 4 mg/mL, as well as atropine at 2 µg/mL. This inhibition confirms that both the extract and atropine effectively antagonize acetylcholine-induced intestinal contractions.

Previous studies have identified that Urtica dioica leaves are rich in phenolic and polyphenolic compounds, which are products of secondary plant metabolism. These compounds include simple phenolics, phenolic acids, stilbenes, flavonoids, coumarins, tannins, lignans, and others, known for their potent biological activities [35]. Among these phytochemicals, flavonoids have a well-established anti-spasmodic property [36].

From an earlier study it is also established that the antidiarrheal activity is directly linked with high content of flavonoids and tannins [37]. Specifically, flavonoids like quercetin, kaempferol, Luteolin, apigenin, isorhamnetin and rutin are found in the leaves of Urtica dioica [24]. Among the flavonoids identified, apigenin, luteolin, and quercetin have been detected in Achillea millefolium s.l., a plant demonstrated to possess notable antispasmodic activity [26]. Similarly, Phyllanthus emblica has been studied for its antispasmodic activity, which is attributed partly to kaempferol—a flavonoid also present in Urtica dioica exhibiting spasmolytic effects through interactions with muscarinic receptors and calcium channel blockade [22].

In addition, Matricaria chamomilla methanolic extract contains quercetin and isorhamnetin, both of which are also present in Urtica dioica, further supporting the role of these shared phytochemicals in contributing to the plant’s antispasmodic effects [38].

Hence, from our experiment it was proved that leaves of Urtica dioica possess anti spasmodic effect probably because of the presence of phytochemicals like flavonoids.

The result indicates that both 2 mg/mL and 4 mg/mL concentrations of ethanolic leaf extract of Urtica dioica produced a dose-dependent reduction in acetylcholine-induced contractions of the chicken ileum, demonstrating clear antispasmodic activity.

The contractile force generated by acetylcholine was significantly reduced with both low and high doses of Urtica dioica extract and atropine, compared to acetylcholine alone. These results suggest that the extract, may inhibit muscarinic receptors in a manner similar to atropine, thereby reducing intestinal contractions. It is well-established that muscarinic receptor inhibition in the gastrointestinal tract promotes the smooth muscle relaxation.

Overall, the data support the potential of Urtica dioica as a therapeutic agent for managing gastrointestinal conditions such as diarrhoea and IBS. However, additional clinical investigations are warranted to validate these effects in human subjects.

We sincerely thank Dr. H.P. Chhetri, Director of Himalayan Pharmacy Institute, Sikkim, and Dr. N.R. Bhuyan, Principal of Himalayan Pharmacy Institute, Sikkim for extending the essential facilities that enabled us to conduct this research work.

1. Sensoy I. A review on the food digestion in the digestive tract and the used in vitro models. Current Research in Food Science. 2021; 4 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crfs.2021.04.004

2. Ogobuiro I, Gonzales J, Shumway KR, Tuma F. Physiology, Gastrointestinal. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

3. Huizinga JD, Chen JH, Fang Zhu Y, Pawelka A, McGinn RJ, Bardakjian BL, <I>et al</I>. The origin of segmentation motor activity in the intestine. Nature Communications. 2014; 5 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4326

4. McQuilken SA. Gut motility and its control. Anaesthesia & Intensive Care Medicine. 2021; 22 (5). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpaic.2021.04.002

5. Nezami BG, Srinivasan S. Enteric Nervous System in the Small Intestine: Pathophysiology and Clinical Implications. Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2010; 12 (5). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-010-0129-9

6. Waugh A, Grant A. Ross and Wilson: Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness. 11th ed. London: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2010.

7. Salm S, Rutz J, van den Akker M, Blaheta RA, Bachmeier BE. Current state of research on the clinical benefits of herbal medicines for non-life-threatening ailments. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2023; 14 Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1234701

8. Salmerón-Manzano E, Garrido-Cardenas JA, Manzano-Agugliaro F. Worldwide Research Trends on Medicinal Plants. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17 (10). Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103376

9. Rauf A, Akram M, Semwal P, Mujawah AA, Muhammad N, Riaz Z, <I>et al</I>. Antispasmodic Potential of Medicinal Plants: A Comprehensive Review. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2021; 2021 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/4889719

10. Guo H., Zhang J., Gao W., Qu Z., Liu C. Gastrointestinal effect of methanol extract of <I>Radix Aucklandiae</I> and selected active substances on the transit activity of rat isolated intestinal strips. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2014; 52 (9). Available from: https://doi.org/10.3109/13880209.2013.879601

11. Aquino R, Tortora S, Fkih-Tetouani S, Capasso A. Saponins from the roots of <I>Zygophyllum gaetulum</I> and their effects on electrically-stimulated guinea-pig ileum. Phytochemistry. Phytochemistry. 2001; 56 (4). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00415-5

12. Sadraei H, Shokoohinia Y, Sajjadi SE, Mozafari M. Antispasmodic effects of <I>Prangos ferulacea</I> acetone extract and its main component osthole on ileum contraction. <I>Research in Pharmaceutical Sciences</I>. 2013;8(3):137-144.

13. Barile E, Capasso R, Izzo AA, Lanzotti V, Sajjadi SE, Zolfaghari B. Structure-activity relationships for saponins from <I>Allium hirtifolium</I> and <I>Allium elburzense</I> and their antispasmodic activity. Planta Medica. 2005; 71 (11). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2005-873134

14. Callan NW, Johnson DL, Westcott MP, Welty LE. Herb and oil composition of dill (<I>Anethum graveolens</I> L.): Effects of crop maturity and plant density. Industrial Crops and Products. 2007; 25 (3). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2006.12.007

15. Begrow F, Engelbertz J, Feistel B, Lehnfeld R, Bauer K, Verspohl E. Impact of Thymol in Thyme Extracts on Their Antispasmodic Action and Ciliary Clearance. Planta Medica. 2010; 76 (04). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1186179

16. Natividad GM, Broadley KJ, Kariuki B, Kidd EJ, Ford WR, Simons C. Actions of <I>Artemisia vulgaris</I> extracts and isolated sesquiterpene lactones against receptors mediating contraction of guinea pig ileum and trachea. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2011; 137 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2011.06.042

17. Maschi O, Cero ED, Galli GV, Caruso D, Bosisio E, Dell’Agli M. Inhibition of human cAMP-phosphodiesterase as a mechanism of the spasmolytic effect of <I>Matricaria recutita</I> L. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2008; 56 (13). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/jf800051n

18. González-Cortazar M, Tortoriello J, Alvarez L. Norsecofriedelanes as Spasmolytics, Advances of Structure-Activity Relationships. Planta Medica. 2005; 71 (08). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2005-871224

19. Corea G, Fattorusso E, Lanzotti V, Capasso R, Izzo AA. Antispasmodic saponins from bulbs of red onion, <I>Allium cepa</I> L. var. Tropea. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2005; 53 (4). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/jf048404o

20. Begum S, Sultana I, Siddiqui BS, Shaheen F, Gilani AH. Structure and spasmolytic activity of eucalyptanoic acid from <I>Eucalyptus camaldulensis</I> var. obtusa and synthesis of its active derivative from oleanolic acid. Journal of Natural Products. 2002; 65 (12). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/np020127x

21. Cometa MF, Parisi L, Palmery M, Meneguz A, Tomassini L. In vitro relaxant and spasmolytic effects of constituents from <I>Viburnum prunifolium</I> and HPLC quantification of the bioactive isolated iridoids. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2009; 123 (2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2009.03.021

22. Mehmood MH, Siddiqi HS, Gilani AH. The antidiarrheal and spasmolytic activities of <I>Phyllanthus emblica</I> are mediated through dual blockade of muscarinic receptors and Ca2+ channels. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2011; 133 (2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2010.11.023

23. Gilani AU, Shah AJ, Ahmad M, Shaheen F. Antispasmodic effect of <I>Acorus calamus</I> Linn. is mediated through calcium channel blockade. Phytotherapy Research. 2006; 20 (12). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.2000

24. Devkota HP, Paudel KR, Khanal S, Baral A, Panth N, Adhikari-Devkota A, <I>et al</I>. Stinging nettle (<I>Urtica dioica</I> L.): Nutritional composition, bioactive compounds, and food functional properties. Molecules. 2022; 27 (16). Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27165219

25. Taheri Y, Quispe C, Herrera-Bravo J, Sharifi-Rad J, Ezzat SM, Merghany RM, <I>et al</I>. <I>Urtica dioica</I>-derived phytochemicals for pharmacological and therapeutic applications. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2022; 2022 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4024331

26. Lemmens-Gruber R, Marchart E, Rawnduzi P, Engel N, Benedek B, Kopp B. Investigation of the spasmolytic activity of the flavonoid fraction of <I>Achillea millefolium</I> s.l. on isolated guinea-pig ilea. Arzneimittelforschung. 2011; 56 (08). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1296755

27. Dhouibi R, Moalla D, Ksouda K, Salem MB, Hammami S, Sahnoun Z, <I>et al</I>. Screening of analgesic activity of Tunisian <I>Urtica dioica</I> and analysis of its major bioactive compounds by GCMS. Archives of Physiology and Biochemistry. 2018; 124 (4). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/13813455.2017.1402352

28. Shaikh JR, Patil MK. Qualitative tests for preliminary phytochemical screening: An overview. International Journal of Chemical Studies. 2020; 8 (2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.22271/chemi.2020.v8.i2i.8834

29. Sharma A, Rathore M, Sharma N, Kumari J, Sharma K. Phytochemical Evaluation of <I>Eucalyptus citriodora</I> Hook. and <I>Lawsonia inermis</I> Linn. <I>Biosciences Biotechnology Research Asia</I>. 2017 Feb 11;6(2):639-45.

30. Mishra A, Adhikari A, Ali B, Gurung P, Kalita R, Bhattacharjee A. In-vitro evaluation of antispasmodic activity of rhizomes of <I>Bergenia ligulate</I>. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2023; 1 (7). Available from: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8121954

31. Tambuli M, Dey N, Thakur N, Ghosh N, Jahan H, Ali NG, <I>et al</I>. Antispasmodic activity of <I>Musa paradisiaca</I> peel aqueous extract. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 2022; 11 (12). Available from: https://doi.org/10.20959/wjpr202212-25269

32. Chakraborty M, Ahmed MG, Bhattacharjee A. Effect of quercetin on myocardial potency of curcumin against ischemia reperfusion induced myocardial toxicity. Synergy. 2018; 7 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.synres.2018.09.001

33. Ehlert FJ. Contractile role of M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors in gastrointestinal, airway and urinary bladder smooth muscle. Life Sciences. 2003; 74 (2-3). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.023

34. Kudlak M, Tadi P. Physiology, Muscarinic Receptor. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

35. Đurović S, Kojić I, Radić D, Smyatskaya YA, Bazarnova JG, Filip S, <I>et al</I>. Chemical constituents of stinging nettle (<I>Urtica dioica</I> L.): A comprehensive review on phenolic and polyphenolic compounds and their bioactivity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25 (6). Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25063430

36. Rojas A, Cruz S, Rauch V, Bye R, Linares E, Mata R. Spasmolytic potential of some plants used in Mexican traditional medicine for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders. Phytomedicine. 1995; 2 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0944-7113(11)80049-8

37. Bayad AE. The antidiarrheal activity and phytoconstituents of the methanol extract of <I>Tecurium oliverianum</I>. Global Veterinaria. 2016; 16 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.gv.2016.16.01.102115

38. Mehmood MH, Munir S, Khalid UA, Asrar M, Gilani AH. Antidiarrhoeal, antisecretory and antispasmodic activities of <I>Matricaria chamomilla</I> are mediated predominantly through K(+)-channels activation. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2015; 15 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-015-0595-6

© 2025 Published by Krupanidhi College of Pharmacy. This is an open-access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.