Journal of Pharmaceutical Research

DOI: 10.18579/jopcr/v24.i4.153

Year: 2025, Volume: 24, Issue: 4, Pages: 245-251

Review Article

Poojari K Sneha1, Gaikwad V Janhavi1, Choudhari S Yash1*, Harshal P Chavan1

1Sir Dr.M.S. Gosavi College of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, Maharashtra, 422005, India

*Corresponding author

Choudhari S Yash

Email: [email protected]

Plants naturally produce a variety of bioactive substances called phytochemicals to defend themselves against pathogens predators and environmental stress. Consuming foods high in phytochemicals on a regular basis has been strongly linked to better health outcomes in recent years according to a large body of scientific research. It has been demonstrated that phytochemicals like carotenoids polyphenols isoprenoids phytosterols saponins dietary fibres and polysaccharides have immunomodulatory cardioprotective anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. These substances significantly lower the risk of various chronic and lifestyle-related diseases and prevent oxidative stress. A number of popular fruits are now acknowledged as important providers of these beneficial phytochemicals. Fruits with rich phytochemical profiles and potential medicinal uses like Vaccinium macrocarpon, Psidium guajava and Selenicereus Undatus are particularly interesting. In addition to offering vital vitamins and minerals these fruits also include a wide variety of bioactive substances that support general health and disease prevention. Fruit-rich diets have therefore continuously been linked to a lower risk of noncommunicable diseases such as diabetes heart disease and some forms of cancer. Many people have tried to enhance their quality of life in response to this mounting body of evidence by consuming more fruit utilizing dietary supplements or nutraceutical products and implementing phytotherapy or nutritional therapy as substitutes or supplements to traditional pharmaceutical treatments. Additionally, the creation of specialized horticultural models for the production of nutraceutical fruits offers a promising chance to acquire standardized superior raw materials for both processed and fresh goods. In order to promote long-term health and disease prevention this article highlights the role that phytochemicals play in human nutrition and stresses the significance of developing good fruit-eating habits from a young age.

Humans have depended on plants for survival and health advantages since the beginning of time. This pattern has persisted to this day, with almost 80% of people worldwide depending on medications derived from plants. Fruits and other horticultural plants are particularly significant in the plant kingdom. Fruit groups have nutritional components including sugars, essential oils, carotenoids, vitamins, and minerals that enhance their overall medicinal characteristics, as well as bioactive components like flavonoids, phenolics, anthocyanins, and phenolic acids. In emerging nations like India, the biggest problems are growing populations, insufficient food, hunger, and a variety of diseases. Usually, we use drugs to seek treatment or to avoid all of these uncertainties. However, as people's health has become more important to them, they are choosing natural resources, such as nutraceuticals, to prevent and treat illness. Given the foregoing, this study presents a summary of the research-based information about the nutritional value of phytochemicals present in fruits such Psidium guajava, Selenicereus Undatus, and Vaccinium macrocarpon.

Dragon fruit is the Selenicereus genus of cacti.[1] It is a member of the family Cactaceae.[2] which are native to southern Mexico and the Pacific coasts of Central America. Three commercially available varieties of Hylocereus pitaya are Yellow Pitaya (white flesh, yellow-skinned fruit with black seeds), Crimson pitaya (purple skin, purple-skinned fruit), and Purple Pitaya (purple skin). The five species, identified through Britton and Rose, have large, funnel-shaped flowers and abundant, yellow pollen.[2] For generations, dragon fruit, sometimes called red pitaya, has been used as a traditional medicine to cure a variety of degenerative diseases. It has a rich cultural history.[1]

Collection and Identification: Hylocereus Undatus, or dragon fruits, were discovered and verified by Professor P. Jayaraman from the Koyambedu fruit market in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India.[3]

The sample underwent chemical tests at Khulna University's Department of Horticulture, Plant Physiology Laboratory, with three fruits for each plant species, each performing as one of three replications.[4]

Originally from North, Central, and South American tropical and subtropical woods, dragon fruit is now produced extensively throughout Asia, including Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand, the Philippines, and southern China.[5]

The three main cultivars of Hylocereus are Hylocereus Undatus (red skin and white flesh), Hylocereus Polyrhizus (red skin and red meat), and Hylocereus Megalanthus (yellow skin and white flesh).[6]

Dragon fruit vegetation thrives in arid tropical or subtropical climates, requiring 500-1400 mm annual rainfall, alternating wet/dry seasons, bright sunshine, and slightly heavy-textured soils. Dragon fruit, grown in over 20 tropical and subtropical nations due to financial incentives, thrives in moist tropical temperatures, despite occasional fruit set issues

The Middle Eastern native dragon fruit has spread to tropical and subtropical regions of Asia, Australia, and the Middle East. Grown successfully in South-Western USA, Vietnam, Australia, Cambodia, China, Israel, Japan, Nicaragua, Peru, Philippines, Spain, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, and Thailand.

Fruit peel removal: To dissolve the active components, the powdered peels were immersed in 95% ethanol for four days. The samples were filtered and washed with fresh ethanol following sonication. In vacuo, the filtrates were concentrated until 20–30 mL of extract remained. To keep heat-sensitive components from degrading, the concentrated extract was kept in an Erlenmeyer flask.[8]

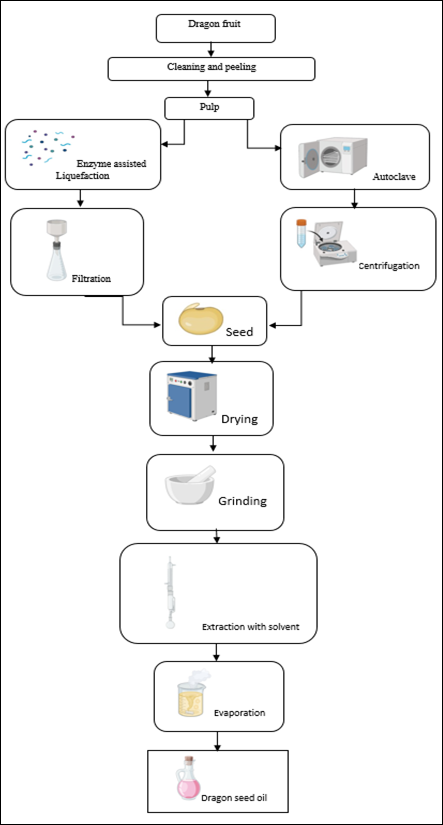

Methods Of Extraction: As shown in [Fig. 1]. Three extraction procedures were compared for extracting pectin from dragon fruit: hydrochloric acid, de-ionized water, and ammonium oxalate. The extraction solutions were combined with 50 grams of air in one litre, and the pH was adjusted with oxalic acid. The extract was filtered, coagulated with isopropanol, cleaned with acetone and isopropanol, and dried at 50°C. The percentage yield was reported, and three duplicates of each extraction condition were performed. The pectin was used for additional analysis and was obtained after drying to a consistent weight and fine powdered consistency.[9]

| Compound class | Compound name |

|---|---|

| Alkaloids | N-benzylmethylene, dopamine hydrochloride, isomethylamine, choline, serotonin, spermine, trigonelline, 6-deoxyfagomine, choline, dopamine hydrochloride, amaranthine, N-cis-feruloyl tyramine, and gomphrenin I. |

| Amino acids and derivatives | L-valine, 2-aminoisobutyric acid, tryptophan, D-(-)-valine, L-tyramine, methionine sulfoxide, L-2- chlorophenylalanine, DL-norvaline, L-methionine, and pipecolic acid. |

| Organic acids: | (Rs)-mevalonic acid, D-galacturonic acid (Gal A), 1-(+)-tartaric acid, methymalonic acid, 4-guanidinobutyric acid, sodium valproate, 6-aminocaproic acid, anchoic acid, aldehydo-D-galacturonate, and citraconic acid. |

| Phenolic acids | Chlorogenic acid, protocatechuic acid-4-glucoside, 1-0-[(E)-p-Cumaroyl)-B-D-glcopyranose, 2,5-dihydroxy benzonic acid O-hexside, coniferin, echinacoside, regaloside L, phthalic anhydride, 1-0-[(E)-Caffeoyl)-B-Dglucopyranose, and trihydroxycinnamoylquinic acid |

| Flavonoids | Catechin (major flavonoids), calycosin, rutin, astragalin, quercetin, myricetin, kaempferol, tectorigenin, grosvenorine, typhaneoside, lonicerin, isoquercetin, nicotiflorin, isorhamnetin-3-O-neohesperidine, gentiopicrin, isorhamnetin, flavonol glycoside, and epicatechin. |

As mentioned in [Table. 3] Dragon fruit is a rich source of vitamin C, phosphorus, calcium, antioxidants, and minerals like potassium, phosphorus, sodium, and magnesium. Its red overlay is a rich source of vitamins B1, B2, B3, and C. Dragon fruit is low in carbs and fats, high in fibre, and contains 50% of the necessary fatty acids. Dragon fruit, known for its high ascorbic acid content and high polyphenolic content, is highly favoured globally due to its antioxidant properties [11].

Psidium guajava, often known as guava, belongs to the Myrtaceae family.[12] There are two common types of Guavas: the red (P. guajava var. pomifera) and the white (P. guajava var. pyrifera). The presence of upper dermis chlorenchyma, palisade, air globules, decrease epidermis, phloem, xylem, sclerenchyma, cuticle, and trichomes was confirmed by the transverse slice of P. guajava leaves. In the dermis, Anomocytic stomata have been found. The typical length of a leaf is 7–15 cm, and its breadth is 3–5 cm. The fresh leaf's color ranged from dull green to dark green. [13] P. guajava is a well-known traditional medicinal herb that is used in many indigenous medical systems. [12]

|

|

Phytochemical compounds |

Varietie(s) |

Method |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Fruit |

Glycosides, alkaloids, saponins, phenolic compounds, tannins, flavonoids, proteins, steroids |

H. undatus |

colour tests |

|

Pulp |

Carbohydrates, proteins and amino acids, alkaloids, terpenoids, steroids, glycosides, flavonoids, tannins, and phenolic compounds, saponins, oils. |

H. undatus |

NA

|

|

Stem |

Phenolics. |

H. undatus |

colour test followed by UV-Vis |

|

Peel

|

13 phenolic compounds: quinic acid, cinnamic acid, quinic acid isomer, 3,4-dihydroxyvinylbenzene, isorhamnetin 3-O-rutinoside, myricetin rhamnohexoside, 3,30-di-O-methyl ellagic acid, isorhamnetin aglycone monomer, apigenin, jasmonic acid, oxooctadecanoic acid, 2 (3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-7- hydroxy-5-benzene propanoic acid and protocatechuic hexoside conjugate. |

H. polyrhizus |

UHPLC-ESI- QTRAP-MSMS |

| Component | Amount | Component | Amount |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iron | 1.9 mg | Phosphorus | 22.5 mg |

| Fiber | 3.0 g | Vitamin C | 20.5 mg |

| Water | 87 g | Vitamin B1 | 0.04 mg |

| Fat | 0.4 g | Vitamin B3 | 0.16 mg |

| Carbohydrate | 11.0 g | Calcium | 8.5 mg |

| Protein | 1.1 g | Vitamin B2 | 0.05 mg |

The Horticulture Studies Institute at the Ayub Agriculture Research Institute in Pakistan provided rare local guava varieties, such as Gola, Chota Gola, Surahi, Karela, Lal Badshah, Sdabahar, and Sufaida. The fruit samples underwent precooling, sorting, and grading. The harvest was primarily done in Peninsular Malaysia's western region, and 195 accessions were cultivated as seedlings. Sixty-eight have been tested for root knot resistance. Three accessions showed possible resistance, and one accession was determined to be resistant to root knots based on early screening. In contrast to the root knot nematode, those accessions will be utilized as a rootstock or figure for guava improvement programs since they are graft-compatible with local business clones of guava.[14]

A variety of methods, including air layering, wedge grafting, budding, and stooling, can be used to produce guava seedlings. The two main seasons for guava flowering and fruiting are March through May and July through August. The July flowering offers a wider variety of vegetation and a more pleasant end. The application of manure and fertilizer depends on the tree's age and soil characteristics. [13]

Guava, a tropical fruit crop, originated in the US and has since spread globally. Major producers include Bangladesh, Brazil, China, India, Thailand, Pakistan, Mexico, Indonesia, the Philippines, and the Netherlands. Top uploading countries include the US, China, Netherlands, and Germany. [16]

Plant extract preparation: The study analysed fifty fruits of guava leaves, which were dried, cleaned, and lyophilized to produce powdered extracts. The extracts were then extracted using solvents like water, ethanol, and methanol. The antioxidant capacity of guava leaf extracts was found to be strongly correlated with their phenolic component content, rather than their flavonoid level. Water extracts had higher phenolic component content than natural ethanol and methanol extracts. The 50% hydroethanolic solvent was found to have the highest antioxidant capacity, with a higher phenolic component concentration than water. [17]

Guava is a fruit with rich nutritional attributes, including antioxidants, minerals, vitamins, and carbohydrates. Its nutritional makeup varies depending on the cultivar, season, and environment. The two primary carbohydrates found in guava fruit are glucose and xylose. 75–85% moisture, 3-7% total dietary fibre, 1-6 protein, and 0.7–0% fibre is all included in an average serving of 100 grams. Clean guava has the highest potassium level among all mineral contents, along with phosphorus, calcium, and iron. Guava also contains the highest amount of vitamin C. The fruit contains flavonoids, glycosides, alkaloids, steroids, tannins, saponins, and flavonoids. Guava's high levels of minerals, dietary fibre, and carotenoids make it a fruit with potential medical uses.

Polyphenol: Although little is known about guava phenolics, earlier studies have shown that they include a variety of polyphenolics, such as flavanols, phenolic acids, flavan-3-ols, and condensed tannins.

Ascorbic acid: Ascorbic acid, a crucial nutrient and antioxidant, is primarily found in fruits and is often used as a nutrient quality signal during food preparation and storage. Guavas are five times more ascorbic acid-rich than oranges, with a vitamin C stage second only to acerola plums.

Carotenoids: Carotenoids are abundant in red, yellow, orange, and green fruits and vegetables. The main role of carotenoids in the human diet is to serve as precursors of provitamin A. Numerous carotenoids, such as phytofluene, β-carotene, lycopene, crypto Flavin, cryptoxanthin, and lutein, are found in guava.

Many fruits and vegetables, such as guava, tomatoes, watermelon, and red grapefruit, are pink because of a fat-soluble pigment called lycopene.

As mentioned in T[able. 4] Evaluation of the phytochemical composition of guava leaf extract using qualitative methods Alkaloids, saponins, and triterpenes are present in relatively smaller concentrations in guava leaf extract, according to phytochemical analysis, whereas phenols, flavonoids, and tannins are present in noticeably higher proportions.[18]

| Qualitative Analysis of Guava Leaf extract | |

|---|---|

| Tested compound | Conclusion |

| Anthroquinones | - |

| Phenols | ++ |

| Saponins | + |

| Triterpenes | + |

| Tannins | ++ |

| Flavonoids | ++ |

| Alkaloids | + |

++: Strongly Detected, +: Detected; −: Not Detected’

[Table. 5] Quantitative evaluation of guava leaf extract's phytochemical composition Quantitative study (spectrophotometrically) was carried out for phenol, tannin, and flavonoids because qualitative research of guava leaves revealed that they are extremely rich in these compounds.[18]

| Compound analysed | Concentration (mg/ml) |

|---|---|

| Phenol | 2.62 ± 0.7 |

| Flavanoids | 0.9 ± 0.3 |

| Tannin | 3.07 ± 0.6 |

Guava leaves are reported to contain a variety of components, including fatty acids, essential oils, terpenoids, phenolic compounds, carbohydrates, glycosides, alkaloids, saponins, sterols, and other substances. The following fatty acids have been identified in guava seeds and guava seed oil: oleic acid, palmitic acid, stearic acid, linoleic acid, and palmitoleic acid. [19]

Minerals and Vitamins: Guava leaves are rich in calcium, potassium, sulphur, sodium, iron, boron, magnesium, manganese, and vitamins C and B. Because GLs include higher amounts of Mg, Na, S, Mn, and B, they are a very good meal for people. They can also be used as animal feed to help prevent micronutrient shortages. Guava leaves are a rich source of minerals, including calcium, potassium, Sulphur, sodium, iron, boron, magnesium, manganese, and vitamin C and B. GLs are a very ideal source of nutrients for humans and can also be used as animal feed to prevent micronutrient deficiencies due to their higher concentrations of Mg, Na, S, Mn, and B. [20]

Essential oils: Crucial oils' caryophyllene is abundant in GLs. 1, eight-cineole trans is the main component of GL vital oil.[20]

The Cranberry (genus Vaccinium) is native to the swamps and bogs of North America belongs to the Ericaceae family.[21] Cranberries are recognized by their native creatures, Vaccinium oxycoccos in Britain and Vaccinium macrocarpon in North America. The former is grown in central and northern Europe, whereas the latter is farmed in the northern parts of the US and Canada.[22] The fruit, a shining burgundy pink with a clean lustrous floor, is globular to ellipsoidal in shape, 10-15mm in period, and nine mm in diameter. It has thin epidermis layers, a sclerenchyma Tous outer sheath, and significant xylem and phloem strands.[23] Native Americans used cranberries for preserving meats and treating wounds. Over the past 10-15 years, cranberry juice has gained scientific support for urinary tract infections.[22]

Latvia's National Botanic Garden in Salas Pils has conducted significant breeding and research on cranberries. In 1972, the first Vaccinium macrocarpon cultivars were released by the Massachusetts Cranberry Research Station in the United States. Later, the garden was planted with US-bred cultivars, some of which were created by researchers.[24] Forty-3 wild cranberries (Vaccinium macrocarpon Ait.) After a study using RAPD-PCR assessed gene variation in clones from four Canadian provinces and five cranberry cultivars, significant genetic variation was found in some wild cranberry collections.[25]

Cranberries are being sown in Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, and New Hampshire, with plans to expand to other states. Chile has already planted 390 hectares, with most used for processed fruit. Stevens and Ben Lear are the top cultivars in both traditional and non-traditional growing areas.[26]

Propagation Seed: Sparkling cranberry seed germinated at a four-percent rate after cold stratification, 56% after cold stratification, and 100% after bloodless stratification. Seed is easy to obtain by cutting cranberries and tapping them out. Rooting is easy with 1000 ppm IBA talc and peat moss/perlite medium. Cooking with berries that bounce is recommended, and sugar sauce can be made while berries pop.[27]

Cranberries, native Northern American fruit, are a nutritious and flavourful source of Vaccinium Oxycoccos, grown in Europe, Finland, and Germany28. In 1999, cranberry manufacturing reached 735 million kilos, with 85% grown in the US and 15% in Canada. This $2 billion industry creates fresh fruit, juices, sauces, dried fruit, and additives like spray-dried powders, frozen fruit, and juice concentrates.[29]

The study examined how the yields of anthocyanins and polyphenols were affected by four different extraction methods. 100 mL of solvent was needed for Soxhlet extraction, whereas 0.50 g of lyophilized cranberry powder was needed for extractions aided by microwave and ultrasound. Following the removal of particles and detritus, the extracts were kept at 4°C. Utilizing a Milestone Ethos, microwave-assisted extraction One microwave unit, 100 millilitres of ethanol, and 0.5% trifluoroacetic acid were used for Soxhlet Extraction. Ultrasound-assisted extraction was optimized for extracting cranberry press residues, using a 100 W ultrasound. The study also compared the effectiveness of ultrasound treatment with or without treatment.[30]

Cranberries have many different plant chemicals, with more than 150 known and studied. Additional phytochemicals may be discovered with further analytical advancements. [Table. 1] provides a summary of the bioactivity, properties, functionalities, and health effects of these phytochemicals.

Anthocyanins Cranberries contain anthocyanins (ACYs), antioxidants in their exocarp layer, which give them their unique red tint. Research on their bioactivity and potential health benefits has highlighted their presence in cranberry juice cocktails, with polymeric anthocyanins contributing to dimmer brownish-pink hues.

Flavanols- Cranberry flavanols, including quercetin, myricetin, and kaempferol, are primarily responsible for yellow undertones and are believed to have numerous health benefits. Their high concentrations are most significant for health outcomes. The cranberry juice cocktail has twice as many general flavanols as any other beverage assessed by Aherne et al., with 4.85 mg/100 mL, more than 12 other juices.

Cranberries are rich in flavanols or flavan-3-ols, which are monomers of proanthocyanidin polymers (PACs). These unique structural traits make cranberries a valuable source of proanthocyanidins, also known as condensed tannins.

Nonflavonoid- Resveratrol as well as nonflavonoid polyphenols are essential for the biological impacts of cranberries. However, there is limited research on the antioxidant activity of resveratrol in cranberries. Cranberries additionally consist of benzoates and simple phenolics, which are fragrant phytochemicals that have potent antioxidant and antibacterial effects. A number of substances found in the soluble phenolic component of cranberries add to the antioxidant value of cranberry products. Less than 50% of these phenolics and benzoates are found in their free form; many of them are converted to ester to carbohydrates, cell wall complex sugars, or other improvements.

Terpenes-Terpenes and their derivatives affect the flavour and scent of cranberries. Pectin’s induce sauce gelation, whereas cranberry husk solids contain 35% fibre that is insoluble. The use of fibre by-products is the subject of current research. Whole cranberry juice contains 0.1% fibre, while cranberry sauce contains about 1%.[31]

This review discusses the rich phytochemical content in fruits and their constituent parts, including the peel, seed, and leaves. It draws attention to the possible health advantages of using phytochemicals in commercial formulations, leading to increased fruit intake, dietary supplements, and nutritional therapy. The review also discusses the potential associations between phytonutrients and diseases. It draws attention to the food industry's capacity to create novel food items using nutraceuticals derived from plants and animals. The review also highlights the need to market these products to attract consumers and convince investors of the financial benefits of investing in nutraceuticals.

Due in large part to Unfavourable environmental circumstances, sedentary lifestyles, and bad eating habits, the frequency of several chronic and lifestyle-related illnesses has significantly grown in recent years. Global interest in preventive healthcare strategies has increased as a result of this rising health burden. Because of their great nutritional value and abundance of bioactive components, fruits are essential for the prevention and treatment of many ailments. They are rich in vital vitamins, minerals, dietary fibre, and phytochemicals that play a major role in maintaining general health. As a result, people are becoming more health-conscious and strongly favouring Phyto nutraceuticals and functional foods over prescription drugs. Because they are thought to have therapeutic advantages with fewer negative side effects than manufactured medications, medicinal plants and fruit-derived products containing phytochemicals are used extensively worldwide. Whether via the use of synthetic chemical formulations like multivitamins or the ingestion of functional foods, dietary supplements, and plant-based nutraceuticals, increasing health status and quality of life have become key goals in the modern period.

1. Rathi KM, Singh SL, Gigi GG. Shekade SV. Nutrition and Therapeutic Potential of the Dragon Fruit: A Qualitative Approach. Pharmacognosy Research. 2023; 16 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.5530/pres.16.1.1

2. Perween T, Mandal, Hasan MA. Dragon fruit: An exotic super future fruit of India. J Pharmacogn Phytochem 2018;7(2):1022-1026. Available from: https://www.phytojournal.com/archives/2018/vol7issue2/PartO/7-1-435-453.pdf

3. Padmavathy K, Kanakarajan S, Karthika S, Selvaraj R, Kamalanathan A. Phytochemical profiling and anticancer activity of dragon fruit Hylocereus undatus extracts against human hepatocellular carcinoma cancer (HepG-2) cells. Int. J. Pharma Sci. Res. 2021;12(5):2770-2778. http://dx.doi.org/10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.12(5).2770-78

4. Yasmin A, Sumi MJ, Akter K, Rabbi RHM, Almoallim HS, Ansari MJ <i>et al</i>. Comparative analysis of nutrient composition and antioxidant activity in three dragon fruit cultivars. PeerJ. 2024; 12 Available from: https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.17719

5. Chowdhury MM, Sikder MI, Islam MR, Barua N, Yeasmin S, Eva TA, <i>et al</i>. A review of ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry, nutritional values, and pharmacological activities of <i>Hylocereus polyrhizus</i>. Journal of Herbmed Pharmacology. 2024; 13 (3). Available from: https://doi.org/10.34172/jhp.2024.49411

6. Nishikito DF, Borges ACA, Laurindo LF, Otoboni AMMB, Direito R, Goulart RdA, <i>et al</i>. Anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidant, and Other Health Effects of Dragon Fruit and Potential Delivery Systems for Its Bioactive Compounds. Pharmaceutics. 2023; 15 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15010159

7. Hossain FM, Numan SMN, Akhtar S. Cultivation, Nutritional Value, and Health Benefits of Dragon Fruit (Hylocereus spp.): a Review. Canadian Journal of Plant Science. 2021; 8 (3). Available from: https://doi.org/10.22059/ijhst.2021.311550.400

8. Cruz VDG, Paragas DS, Gutierrez RL, Antonino JP, Morales KS, Dacuycuy EA, <i>et al</i>. Characterization and assessment of phytochemical properties of dragon fruit (Hylocereus undatus and Hylocereus polyrhizus) peels. International Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology. 2022;18(3): 1307-1318

9. Ismail NSM, Ramli N, Hani NM, Meon ZJSM. Extraction and characterization of pectin from dragon fruit (Hylocereus polyrhizus) using various extraction conditions. Sains Malaysiana. 2012;41(1), 41-45.

10. Jalgaonkar K, Mahawar MK, Bibwe B, Kannaujia P. Postharvest Profile, Processing and Waste Utilization of Dragon Fruit (<i>Hylocereus Spp</i>.): A Review. Food Reviews International. 2022; 38 (4). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/87559129.2020.1742152

11. Luu T, Le T, Huynh N, Quintela-Alonso P. Dragon fruit: A review of health benefits and nutrients and its sustainable development under climate changes in Vietnam. Czech Journal of Food Sciences. 2021; 39 (2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.17221/139/2020-cjfs

12. Rana, R., Thakur, R., Singla, S., & Goyal, S.. Psidium Guajava Leaves: Phytochemical study and Pharmacognostic evaluation. Himalayan Journal of Health Sciences. 2020; 5 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.22270/hjhs.v5i1.48

13. Gupta M, Wali A, Anjali, Gupta S, Annepu SK. Nutraceutical Potential of Guava. Reference Series in Phytochemistry. 2019; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78030-6_85

14. Yousaf AA, Abbasi KS, Ahmad A, Hassan I, Sohail A, Qayyum A <i>et al</i>. Physico-chemical and Nutraceutical Characterization of Selected Indigenous Guava (Psidium guajava L.) Cultivars. Food Science and Technology. 2021; 41 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1590/fst.35319

15. Rajan S, Hudedamani U. Genetic Resources of Guava: Importance, Uses and Prospects. Conservation and Utilization of Horticultural Genetic Resources. 2019; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3669-0_11

16. Bano A, Gupta A, Rai S, Sharma S, Upadhyay TK, Al-Keridis LA, <i>et al</i>. Bioactive Compounds, Antioxidant, and Antibacterial Activity Against MDR and Food-Borne Pathogenic Bacteria of Psidium guajava. L Fruit During Ripening. Molecular Biotechnology. 2025; 67 (8). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12033-023-00779-y

17. Seo J, Lee S, Elam ML, Johnson SA, Kang J, Arjmandi BH. Study to find the best extraction solvent for use with guava leaves (<i>Psidium guajava</i>L.) for high antioxidant efficacy. Food Science & Nutrition. 2014; 2 (2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.91

18. Das M, Goswami S. Antifungal and antibacterial property of guava (Psidium guajava) leaf extract: Role of phytochemicals. International Journal of Health Sciences and Research. 2019;9(2), 39-45.

19. Kareem AT, Kadhim EJ. Psidium guajava: A Review on Its Pharmacological and Phytochemical Constituents. Biomedical and Pharmacology Journal. 2024; 17 (2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.13005/bpj/2924

20. Kumar M, Tomar M, Amarowicz R, Saurabh V, Nair MS, Maheshwari C. Guava (Psidium guajava L.) Leaves: Nutritional Composition, Phytochemical Profile, and Health-Promoting Bioactivities. Foods. 2021; 10 (4). Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040752

22. Dao CA, Patel KD, Neto CC. Phytochemicals from the Fruit and Foliage of Cranberry (<i>Vaccinium macrocarpon</i>) - Potential Benefits for Human Health. ACS Symposium Series. 2012; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-2012-1093.ch005

23. Khaneja M, Gupta, S, Sharma A. Pharmacognostical and Preliminary Phytochemical Investigations on fruit of Vaccinium macrocarpon aiton. Pharmacognosy Journal. 2015; 7 (6). Available from: https://doi.org/10.5530/pj.2015.6.3

24. Šedbarė R, Jakštāne G, Janulis V. Phytochemical Composition of the Fruit of Large Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon Aiton) Cultivars Grown in the Collection of the National Botanic Garden of Latvia. Plants. 2023; 12 (4). Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12040771

25. Debnath SC. An Assessment of the Genetic Diversity within a Collection of Wild Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon Ait.) Clones with RAPD-PCR. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 2007; 54 (3). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-006-0007-3

26. Frank L. Caruso. Trends in cranberry production. In VI International Symposium on Vaccinium Culture. Acta Horticulturae. 1997; (446). Available from: https://doi.org/10.17660/actahortic.1997.446.3

27. Lapin, L. Cultivation Notes.

28. Côté J, Caillet S, Doyon G, Sylvain JF, Lacroix M. Bioactive Compounds in Cranberries and their Biological Properties. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2010; 50 (7). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/10408390903044107

29. Cunningham DG, Vannozzi SA, Turk R, Roderick R, O'Shea E, Brilliant K. Cranberry Phytochemicals and Their Health Benefits. ACS Symposium Series. 2003; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-2004-0871.ch004

30. Linards K, Jorens K, Maris K. Lipids of cultivated and wild Vaccinium Spp. Berries from Latvia. FOODBALT. 2019; Available from: https://doi.org/10.22616/foodbalt.2019.019

31. Pappas E, Schaich KM. Phytochemicals of Cranberries and Cranberry Products: Characterization, Potential Health Effects, and Processing Stability. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2009; 49 (9). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/10408390802145377

21. Elsayed M, Ahmed A, Ahmed E, Hassan D, Sliem M, Zewail D, <i>et al</i>. A review on bioactive metabolites and great biological effects of Cranberry. ERU Research Journal. 2023; 2 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.21608/erurj.2023.190174.1009

© 2025 Published by Krupanidhi College of Pharmacy. This is an open-access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.