Journal of Pharmaceutical Research

DOI: 10.18579/jopcr/v24.i4.145

Year: 2025, Volume: 24, Issue: 4, Pages: 189-194

Case Report

Keshavlal Gujrathi1, Deepali Kadam2, Kishor Jain3*

1Dr. Gujrathi's Clinic, 1180, Raviwar Peth, Pune 411002, Maharashtra, India

2Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Sandip Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Nashik- 422213, Maharashtra, India

3Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, R.J.S.P.M.'s College of Pharmacy, Dudulgaon, Pune 412105, Maharashtra, India

* Corresponding author.

Kishor Jain

[email protected]

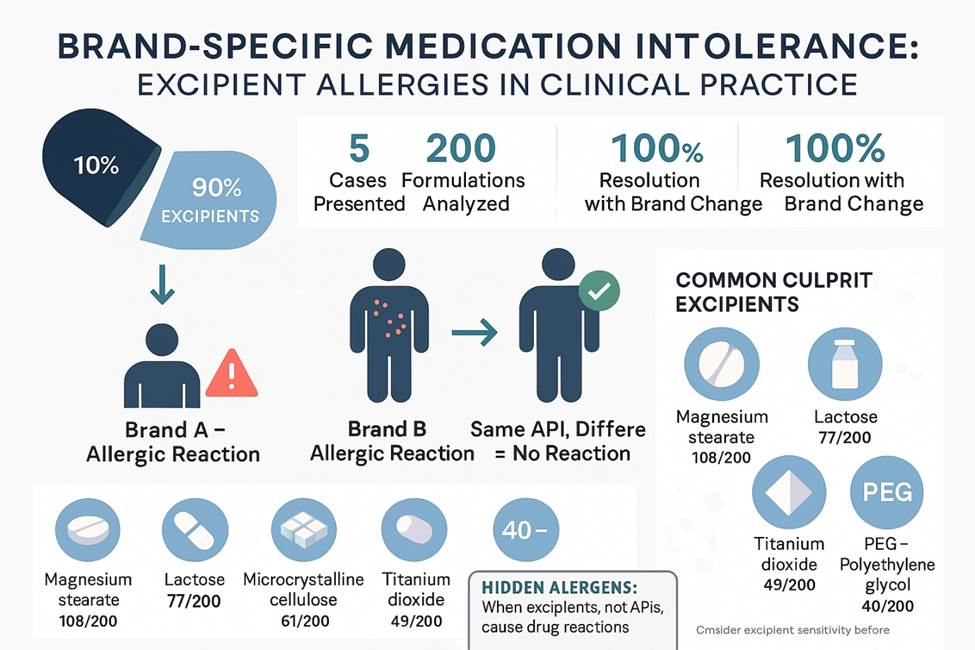

Drug allergies are commonly attributed to active pharmaceutical ingredients, but excipients; the inactive ingredients comprising up to 90% of medication formulations, can also cause adverse reactions that are often overlooked. The recent cough syrup tragedy in Oct 2025 in India, due to an excipient, underlines the seriousness of the matter. We present five patients who experienced allergic reactions to specific medication brands but tolerated identical active ingredients from different manufacturers. All patients showed complete resolution when switched to alternative brands containing different excipients. Cases included reactions to phenobarbital, diclofenac, aspirin, and rabeprazole formulations. Analysis of 200 tablet formulations revealed magnesium stearate, lactose, and microcrystalline cellulose as the most common excipients. Excipient allergies represent an under recognized cause of drug reactions. Clinicians should consider excipient sensitivity when patients report brand-specific medication intolerance, as this can prevent unnecessary active ingredient avoidance.

Keywords: Drug Allergy, Excipients, Pharmaceutical Formulation, Adverse Drug Reactions, Case Series, Brand-Specific Intolerance

Drug allergies are frequently encountered in clinical practice, with adverse drug reactions affecting approximately 10-20% of hospitalized patients and representing a significant cause of healthcare costs, morbidity and sometimes even death. The recent cough syrup tragedy in Oct 2025, in India, due to an excipient, underlines the seriousness of the matter [1]. While, most clinical attention focuses on active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) as causative agents, excipients, the inactive components that constitute approximately 90% of most medication formulations, represent an under-recognized but increasingly important cause of hypersensitivity reactions [2, 3].

According to the European Medicines Agency, excipients are defined as constituents of a pharmaceutical form apart from the active substance [4]. These compounds serve essential functions in drug formulation including altering dissolution kinetics, improving stability, enhancing bioavailability, influencing palatability, facilitating manufacturing processes, and creating distinctive appearances [5]. Common categories of excipients include binders, disintegrants, lubricants, preservatives, stabilizers, colors, and flavouring agents.

Recent systematic reviews have identified over 65 different excipients capable of inducing immediate hypersensitivity reactions, with polyethylene glycol derivatives (PEG-4000 & PEG-600) being the most prevalent allergenic excipient, followed by coloring agents[6]. Use of PEGs is particularly concerning as they are widely used in pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and food products, and can cause severe anaphylactic reactions through an immunoglobulin E-dependent mechanism [7, 8]. The clinical significance of these ethylene glycol derivative allergies has gained renewed attention following reports of anaphylaxis associated with COVID-19 m-RNA vaccines containing ethylene glycol derivatives [9, 10].

Excipients contribute to drug stability, preservation, pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, appearance and acceptability, yet their allergenic potential is often overlooked in clinical practice [11]. Allergy to excipients is a cause of multidrug allergy and if it is not taken into account, it can lead to unexpected severe reactions [12]. This phenomenon is particularly problematic because different manufacturers may use varying excipients while maintaining bioequivalence of the active ingredient, leading to brand-specific hypersensitivity reactions that can be mistakenly attributed to the API.

The clinical manifestations of excipient allergies range from mild cutaneous reactions to life-threatening systemic anaphylaxis [13]. However, there are no data on the prevalence of immediate hypersensitivity reactions due to drug excipients, and standardized diagnostic algorithms for excipient allergy testing remain underdeveloped. This diagnostic challenge often results in inappropriate medication discontinuation, suboptimal therapeutic outcomes, and increased healthcare costs.

The clinical significance of excipient allergies extends beyond individual patient care to public health implications. Recent clinical evidence elucidates their potential in inducing anaphylaxis and indicates that they are often overlooked, as potential allergens in routine clinical practice [14]. Healthcare providers must develop heightened awareness of excipient-induced hypersensitivity to optimize patient safety and therapeutic outcomes.

This case series presents five patients who experienced brand-specific medication intolerance that resolved when switched to alternative formulations containing the same active ingredients but different excipient profiles, highlighting the clinical importance of recognizing excipient-related adverse drug reactions in routine practice.

This was a retrospective case series conducted over a period of clinical practice, documenting patients who presented with unexplained allergic reactions to specific medication brands while tolerating the same active pharmaceutical ingredients from different manufacturers. A total of 8 cases were initially identified, with 5 cases selected for detailed presentation based on completeness of clinical documentation and clear evidence of brand-specific intolerance.

Each case was systematically documented using the following parameters: patient demographics (age, gender), primary medical condition requiring treatment, initial drug prescribed and allergic symptoms observed, alternative brand prescribed and clinical outcome, and timeline of symptom resolution after brand change.

To understand the potential causative agents behind observed allergic reactions, a comprehensive analysis of pharmaceutical excipients was conducted. This involved: Database Creation [15]: a systematic review of 200 commercially available tablet formulations was performed to identify commonly used excipients; Categorization [5]: excipients were classified by function (binders, disintegrants, lubricants, preservatives, etc.) and frequency of use; Cross-referencing [16]: patient reaction patterns were compared with excipient profiles of tolerated versus non-tolerated formulations.

This retrospective case series was conducted in accordance with institutional ethical guidelines for case documentation. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients for publication of their clinical information. Patient confidentiality was maintained throughout the documentation process, with only clinically relevant information included in case presentations.

Each case was analyzed for patterns of symptom presentation, timing of reactions, and resolution following brand substitution. Identified excipients were cross-referenced with published literature on known allergenic potential. Given the exploratory nature of this case series and the qualitative outcomes measured, formal statistical analysis was not applicable. Results are presented as descriptive statistics and frequency distributions for the excipient analysis component.

This study had several limitations including: (1) lack of formal allergy testing. Patch testing or other standardized allergy tests were not performed to definitively confirm excipient-specific allergies; (2) Incomplete excipient information, as complete excipient profiles were not always available for all formulations on their labels; (3) retrospective design: the retrospective nature limited the ability to control for confounding variables; (4) small sample size: the limited number of cases restricts generalizability of findings.

Case 1: A 20-year-old female with epilepsy, previously successfully treated with parenteral phenobarbital, developed allergic rashes while taking phenobarbital 60mg tablets orally. The rash appeared within 48 hours of starting oral therapy and persisted despite dose reduction to 30mg and subsequently 15mg. However, when switched to dispersible 15mg tablets (four tablets to achieve 60mg total dose), the patient tolerated the medication without allergic reactions. The key difference was that dispersible tablets contained calcium carbonate as a carrier agent, while swallowable tablets used starch-based excipients. The rash resolved completely within 72 hours of switching formulations.

Case 2: Five family members experienced allergic reactions to generic diclofenac tablets from a specific manufacturer, manifesting as urticaria and pruritus within 2-4 hours of administration. The same observation of allergic reactions was also noted when administered aceclofenac tablets from the same manufacturer. Notably, one member had previously tolerated diclofenac injections without adverse effects. When switched to a different brand of diclofenac tablets, no reactions occurred in any family member, suggesting excipient-specific sensitivity rather than intolerance to the active ingredient.

Case 3: A 60-year-old female with known sensitivity to aspirin (manifesting as rash and itching) was prescribed enteric-coated aspirin (Ecosprin) for cardiac complaints. Despite her previous aspirin sensitivity to uncoated formulations, she tolerated Ecosprin without adverse reactions, indicating different excipient profiles between the formulations. The patient had no recurrence of cutaneous symptoms over a 6-month follow-up period.

Case 4: A 75-year-old male developed black patches on arms and cheeks with multiple medication formulations from the same manufacturer. The discoloration appeared within 1-2 weeks of starting therapy and persisted throughout treatment. When prescribed different brands of the same medications, reactions did not occur, suggesting sensitivity to common excipients (possibly iron oxide colorants) used across multiple generic formulations from that manufacturer. Skin patches gradually faded over 4-6 weeks after discontinuation.

Case 5: A 75-year-old female prescribed rabeprazole 20mg developed acute disorientation within two hours of administration, including inability to recognize family members, places, and time. The cognitive symptoms persisted for approximately 6 hours. After systematic drug withdrawal and reintroduction, rabeprazole was identified as the causative agent. Interestingly, a different brand of rabeprazole was later tolerated without adverse effects, with no recurrence of neurological symptoms over subsequent months.

All five patients demonstrated complete resolution of allergic symptoms when switched to alternative brands containing the same active ingredients but different excipient profiles ([Table. 1]).

Our analysis of 200 tablet formulations revealed the distribution of commonly used excipients ([Table. 2], [Table. 3], and [Table. 4]).

| Case No. | Generic drug formulation* given | Allergic symptoms observed | Drug changed to branded formulation* | Allergy Symptoms after changing to Branded formulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Phenobarbital 60mg tablet | Allergic rash, drowsiness | Dispersible branded phenobarbital 15mg tablets (4) | Nil |

| 2 | Diclofenac 50mg generic tablets | Family-wide urticaria, pruritus | Different branded diclofenac tablets | Nil |

| 3 | Aspirin 350mg uncoated tablets | Rash, itching | Ecosprin (enteric-coated) | Nil |

| 4 | Multiple Vitamin B-Complex formulations (tablets/capsules) | Black patches on skin | Different branded tablets | Nil |

| 5 | Rabeprazole 20mg tablets | Acute disorientation | Different rabeprazole branded tablets | Nil |

*The names of the generic & branded formulations are not

disclosed

A relevant historical example supports our findings: When cetirizine was introduced in India in 1995, post-patent expiry generic formulations initially used blue colouring, which caused allergic reactions in several patients. When manufacturers changed the colors to white, the allergic reactions ceased, demonstrating clear evidence of excipient-related hypersensitivity.

| Rank | Excipient | Frequency of use (out of 200 formulations) | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Magnesium stearate | 108 | Tablet and capsule lubricant |

| 2 | Lactose (various forms) | 77 | Tablet binder; diluent |

| 3 | Microcrystalline cellulose | 61 | Adsorbent; diluent; disintegrant |

| 4 | Titanium dioxide | 49 | Coating agent; opacifier; pigment |

| 5 | Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose | 45 | Coating agent; film-former; binder |

| 6 | Ethylene glycol derivatives (DEG & PEG) | 40 | Plasticizer; solvent; lubricant |

| 7 | Povidone (PVP) | 36 | Disintegrants; dissolution aid; binder |

| 8 | Hydroxypropyl cellulose | 25 | Coating agent; binder; thickener |

| 9 | Croscarmellose sodium | 22 | Tablet and capsule disintegrants |

| 10 | Colloidal silicon dioxide | 22 | Anticaking agent; glidant; stabilizer |

| Function/ Category of the excipient | Number of different excipients used | Most common examples |

|---|---|---|

| Binders | 15 | Microcrystalline cellulose, Povidone, Starch |

| Lubricants | 8 | Magnesium stearate, Stearic acid, PEG |

| Disintegrants | 7 | Croscarmellose sodium, Crospovidone, Starch |

| Coating Agents | 6 | HPMC, Titanium dioxide, Ethyl cellulose |

| Preservatives | 9 | Methyl paraben, Benzyl alcohol, Sodium benzoate |

| Diluents | 12 | Lactose, Calcium phosphate, Mannitol |

| Stabilizers | 8 | Colloidal silicon dioxide, Sodium alginate |

| Colors | 6 | Iron oxides, Erythrosine sodium |

| Excipient | Frequency | Known Allergenic Potential | Clinical Manifestations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactose | 77 | Lactose intolerance | GI symptoms, skin reactions |

| PEG derivatives | 40 | IgE-mediated reactions | Anaphylaxis, urticaria |

| Parabens | 6 | Contact sensitization | Dermatitis, systemic reactions |

| Benzyl alcohol | 2 | Hypersensitivity | Bronchospasm, skin reactions |

| Iron oxides | 26 | Rare allergic reactions | Skin discoloration, dermatitis |

| Starch derivatives | 58 | Plant protein contamination | Urticaria, respiratory symptoms |

This case series demonstrates that excipient allergies can masquerade as active ingredient intolerance, potentially leading to inappropriate medication discontinuation. The differential tolerance observed between dispersible and swallow able formulations in Cases 1 and 3 suggests that specific excipients, rather than active ingredients, were responsible for the adverse reactions.

Our analysis of 200 tablet formulations revealed extensive use of various excipients, with magnesium stearate (108 instances), lactose (77 instances), and microcrystalline cellulose (61 instances) being most common. Any of these components could potentially trigger allergic reactions in susceptible individuals. This finding aligns with recent literature documenting carboxymethylcellulose as a cause of systemic allergic reactions, particularly in corticosteroid preparations [17].

The challenge in identifying excipient allergies lies in their unexpected nature and the lack of standardized diagnostic testing. For most excipients, the dilutions used for skin testing are not standardized and proper algorithms to guide diagnostic workup remain underdeveloped [5]. Unlike active ingredient allergies, excipient sensitivities are rarely considered during initial evaluation of drug reactions. This diagnostic gap is compounded by the fact that excipients are often not prominently listed on medication packaging, making identification of potential culprits difficult for both patients and healthcare providers [12].

This oversight can result in: (1) unnecessary avoidance of therapeutically important medications; (2) inadequate treatment of underlying conditions; (3) increased healthcare costs due to alternative therapy requirements; (4) patient anxiety regarding medication safety; and (5) misclassification as "multidrug allergy syndrome" when the actual culprit is a single excipient used across multiple formulations [16].

Healthcare providers should consider excipient allergies when patients report: brand-specific medication intolerance; tolerance of injectable forms but not oral formulations of the same drug; reactions to multiple medications from the same manufacturer; unexplained allergic reactions despite negative testing for active ingredient sensitivity; reactions

to products containing common excipients like PEGs found in laxatives, depot medications, and topical preparations [18]; and anaphylaxis with medications containing gelatine, benzalkonium chloride, or benzyl alcohol [18].

Recent evidence has highlighted excipients as hidden dangers in pharmaceutical formulations and vaccines, emphasizing the need for systematic evaluation of excipient content when investigating drug hypersensitivity reactions [11]. The resurgence of interest in excipient allergies represents a new challenge in drug allergy diagnosis and management [12].

Excipients used in pharmaceutical formulations, though thought to be bland and neutral in nature, sometimes can lead to untoward effects. Recently, case deaths with diethylene glycol contamination in North-Central India represent a life-threatening example, where the grade of the PEG used as a vehicle in the syrup did not comply with pharmaceutical standards. With more than 276 types of excipients currently in use, the scope for allergic reactions is considerable [15].

Excipient allergies represent an under-recognized cause of adverse drug reactions that can significantly impact patient care. Clinicians should maintain awareness of this possibility when evaluating drug allergies, particularly in cases of brand-specific intolerance. Our case series demonstrates that switching medication brands while maintaining the same active ingredient can successfully resolve allergic symptoms in patients with excipient sensitivity.

Development of standardized diagnostic testing for excipient allergies and improved labeling of excipient content in medications would enhance clinical management and prevent unnecessary medication avoidance. As the pharmaceutical industry continues to develop complex formulations with novel excipients, ongoing vigilance and education about excipient hypersensitivity will become increasingly important for optimal patient care. Healthcare providers should routinely inquire about brand-specific reactions and consider excipient sensitivity as a potential cause before discontinuing therapeutically important medications.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients who consented to publication of their clinical information and the pharmacy colleagues who assisted in excipient identification and formulation analysis.

Author Contributions

KG: Clinical case identification, patient management, KJ: Manuscript conceptualization. Literature search and review, excipient analysis, and data compilation, DK: Manuscript writing and editing. All 3 authors: Final manuscript checking and approval.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This article represents a retrospective case series based on routine clinical care. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients for publication of their clinical information.

Consent

Written consent was obtained from all patients.

1. Epidemiology of hypersensitivity drug reactions. Current Opinion in Allergy & Clinical Immunology. 2005; 5 (4). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.all.0000173785.81024.33

2. Immediate Hypersensitivity Reactions Caused by Drug Excipients: A Literature Review. Journal of Investigational Allergology and Clinical Immunology. 2020; 30 (2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.18176/jiaci.0476

3. The safety of pharmaceutical excipients. Il Farmaco. 2003; 58 (8). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0014-827x(03)00079-x

4. European Medicines Agency. Guideline on excipients in the dossier for application for marketing authorization of a medicinal product. 2007. 1-12.

5. Symptoms and danger signs in acute drug hypersensitivity. Toxicology. 2005; 209 (2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2004.12.036

6. New Challenges in Drug Allergy: the Resurgence of Excipients. Current Treatment Options in Allergy. 2022; 9 (2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40521-022-00313-6

7. Polyethylene Glycol-Induced Systemic Allergic Reactions (Anaphylaxis). Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 2021; 9 (2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2020.09.029

8. Polyethylene glycol as a cause of anaphylaxis. Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology. 2016; 12 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-016-0172-7

9. Hypersensitivity to polyethylene glycol in adults and children: An emerging challenge. Acta Biomedica. 2021; 92 (7). Available from: https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v92is7.12384

10. Optimizing investigation of suspected allergy to polyethylene glycols. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2022; 149 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2021.05.020

11. Hidden Dangers: Recognizing Excipients as Potential Causes of Drug and Vaccine Hypersensitivity Reactions. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 2021; 9 (8). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2021.03.002

12. Antibiotic Allergy in Pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2018; 141 (5). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-2497

13. Potential food allergens in medications. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2014; 133 (6). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.03.011

14. Excipient Hypersensitivity Masquerading as Multidrug Allergy. The American Journal of Medicine. 2021; 134 (8). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2021.02.015

15. American Pharmaceutical Review. Pharmaceutical Raw Materials and APIs: Pharmaceutical Excipients. 2023. Available at: https://www.americanpharmaceuticalreview.com/25335-Pharmaceutical-Raw-Materials-and-APIs/25283-Pharmaceutical-Excipients/

16. Hypersensitivity reactions to mAbs: 105 desensitizations in 23 patients, from evaluation to treatment. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2009; 124 (6). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2009.09.009

17. Carboxymethylcellulose excipient allergy: a case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2021; 15 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-03180-y

18. Drug Allergy: An Updated Practice Parameter. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 2010; 105 (4). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2010.08.002

© 2025 Published by Krupanidhi College of Pharmacy. This is an open-access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.